What's in a name? Some thoughts on the 'exSPAnder' assembly tool

This week a new tool was published in the Bioinformatics journal:

ExSPAnder: a universal repeat resolver for DNA fragment assembly

The tool's name really refers to the name of an algorithm that is implemented as part of the SPAdes genome assembler. I don't think that this is particularly obvious from the title of the paper. The results section in the paper further complicates this somewhat. E.g. this is how the comparative assembler results are reported in Table 2 of the paper:

The entry called 'SPAdes 2.4' refers to a version of the SPAdes assembler that doesn't use the exSPAnder algorithm, whereas the entry marked 'EXPANDER" refers to a newer version of the SPAdes assembler that does include the algorithm. I find this confusing and it is one of three issues that I have concerning the use of the exSPAnder name:

1. Do we really need to start giving names to algorithms that are part of another tool? This has the potential to create a lot more confusion for people. Particularly when there is no tool called 'exSPAnder' that you can download from anywhere. If somebody implemented the algorithm as part of another piece of software would they be expected to retain the exSPAnder name somewhere (MegaAssembler featuring exSPAnder)?

2. You would hope that the website that the paper links to gives you more information about exSPAnder. But that's not the case:

- Number of mentions of exSPANder in the publication: 35

- Number of mentions of exSPAnder in the linked software web page: 0

- Number of mentions of exSPAnder in the latest SPAdes v3.1.0 manual: 0

Again, I think this can only lead to confusion. The mention of exSPAnder as if it was its own separate tool suggests that this is software that you can download. E.g. this is from the Conclusion section of the paper:

Benchmarks across eight popular assemblers demonstrate that exSPAnder produces high-quality assemblies for datasets of different types.

But exSPAnder is not an assembler that anyone can download and use at the moment. Rather you can download the SPAdes assembler which may or may not feature the exSPAnder algorithm (I don't know because the website and the manual doesn't say).

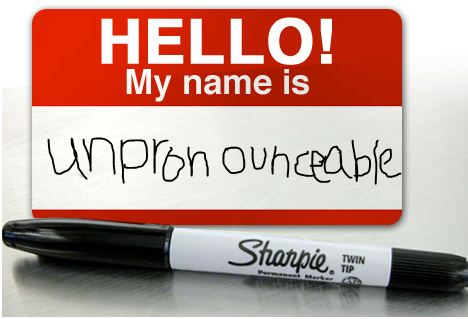

3. My final issue is perhaps the most minor one and it relates to this horrible trend of using mixed capitalization for bioinformatics tool names. If you are going to do this, please be consistent and please realize that journal formatting conventions may mess up your planned use of capitalization. Here are the different ways you can see 'exSPAnder' referred to in this paper:

- ExSPAnder: 1

- exSPAnder: 1

- EXPANDER: 1

- EXSPANDER: 28

So I'm assuming that the latter format is the one that the authors are really using and the other variations are due to problems of the journal formatting the article. Using small caps like this is a great way to guarantee that no-one else will bother to format the name like this. Okay, time to finish this post as I need to go and work on my new assembly tool:

MaSSEMbLerXL— an assembler that assigns different font sizes to each DNA base